MEMORY PORTRAIT

Electroencephalography . EEG instrumen . Family Album .

photo series . 2012

One day, I stumbled upon a collection of old photographs from my childhood, yet I could not recall when or where they had been taken. When I rediscovered them, it felt like pushing open a door of perception that had long been sealed.

This encounter prompted me to question the nature of memory itself: What constitutes a portrait of memory? How can its essence be captured or recorded? These questions became the starting point of my visual exploration of “memory,” leading me to experiment with photography and portraiture as a way of approaching the invisible.

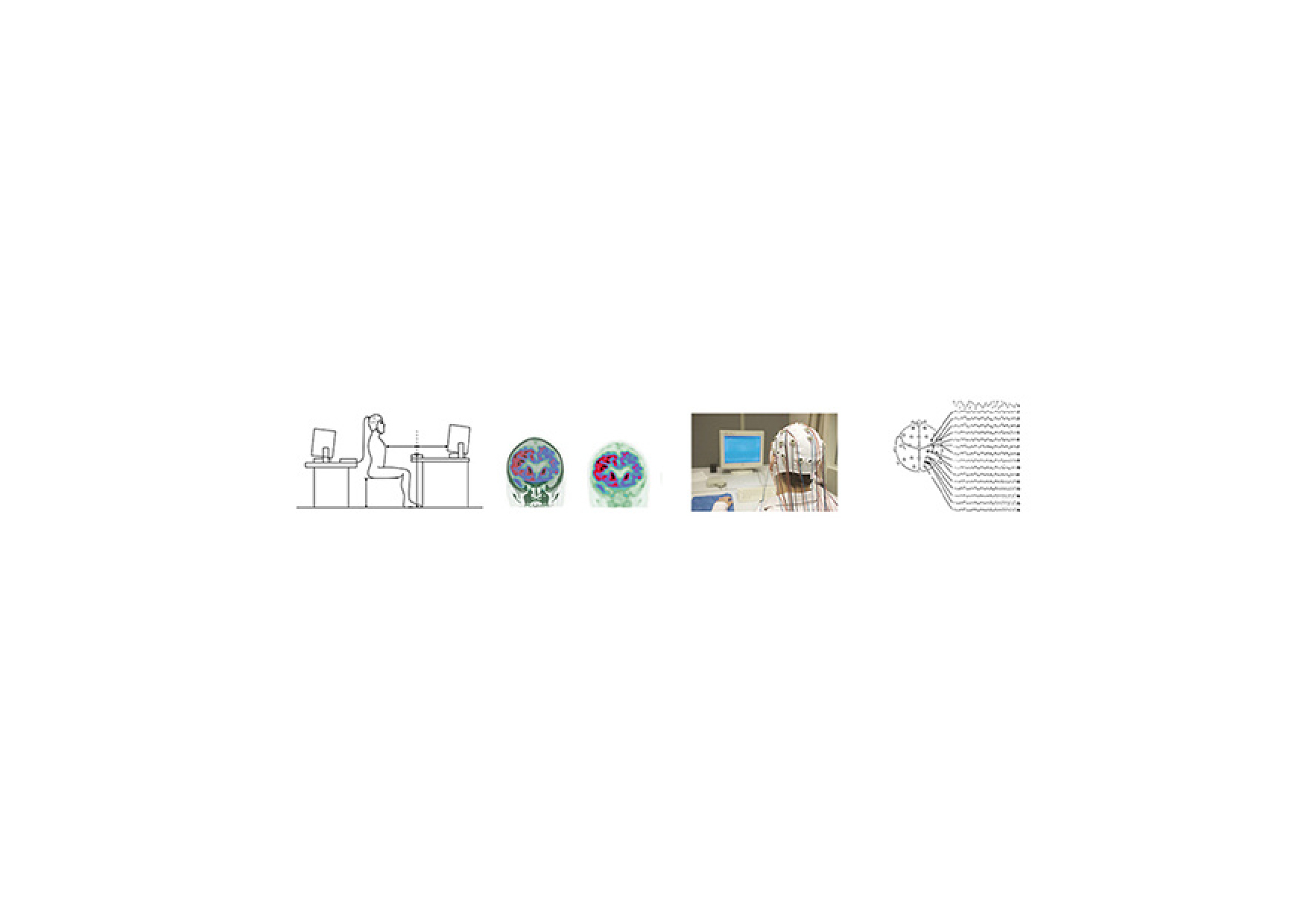

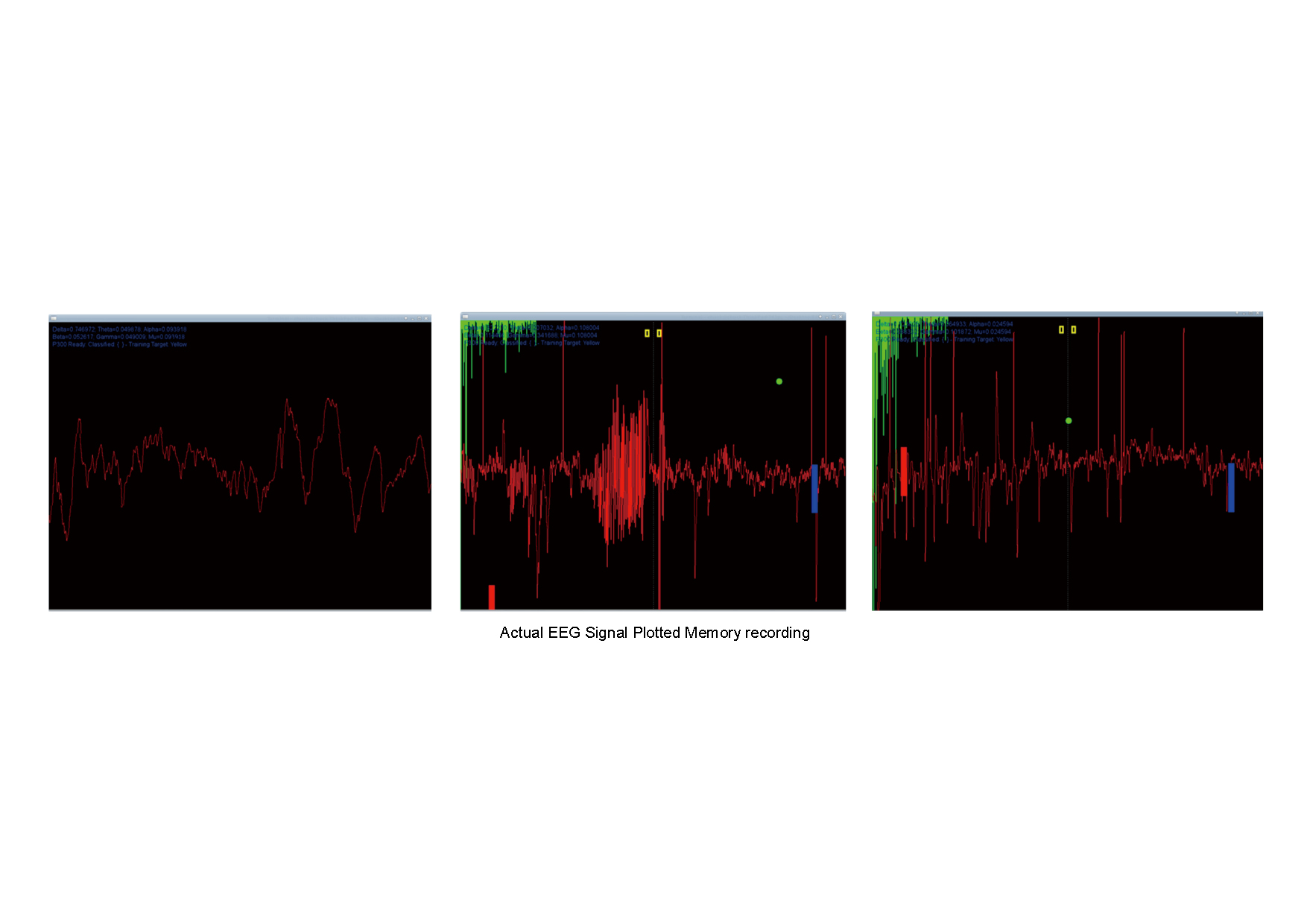

In pursuit of this idea, I underwent electroencephalography (EEG) at the hospital where my mother worked. As I recalled the childhood photographs, the EEG recorded the frequencies of my brainwave activity associated with memory. Stronger memories produced clearer, more pronounced waveforms, while weaker ones appeared faint and diffused.

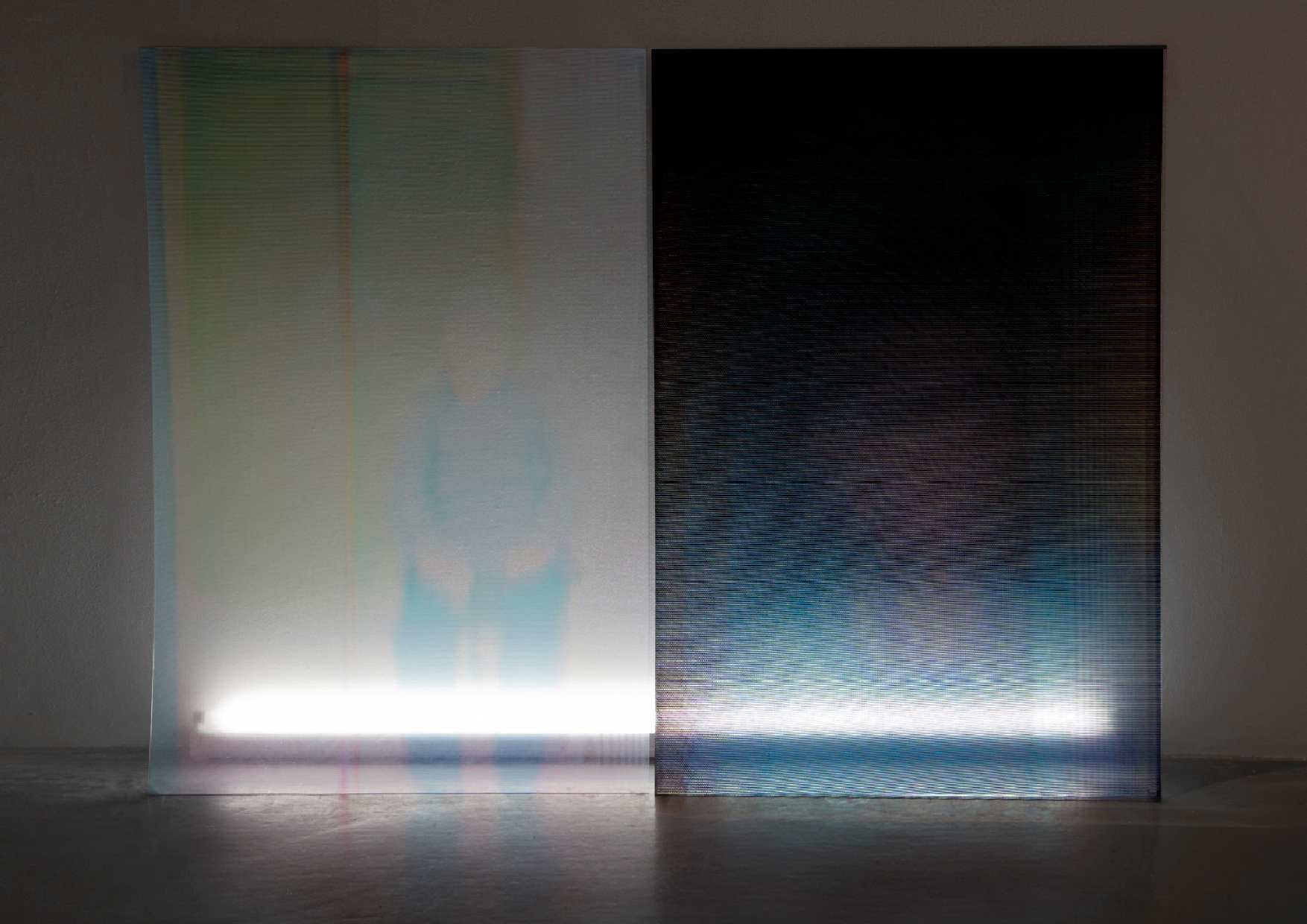

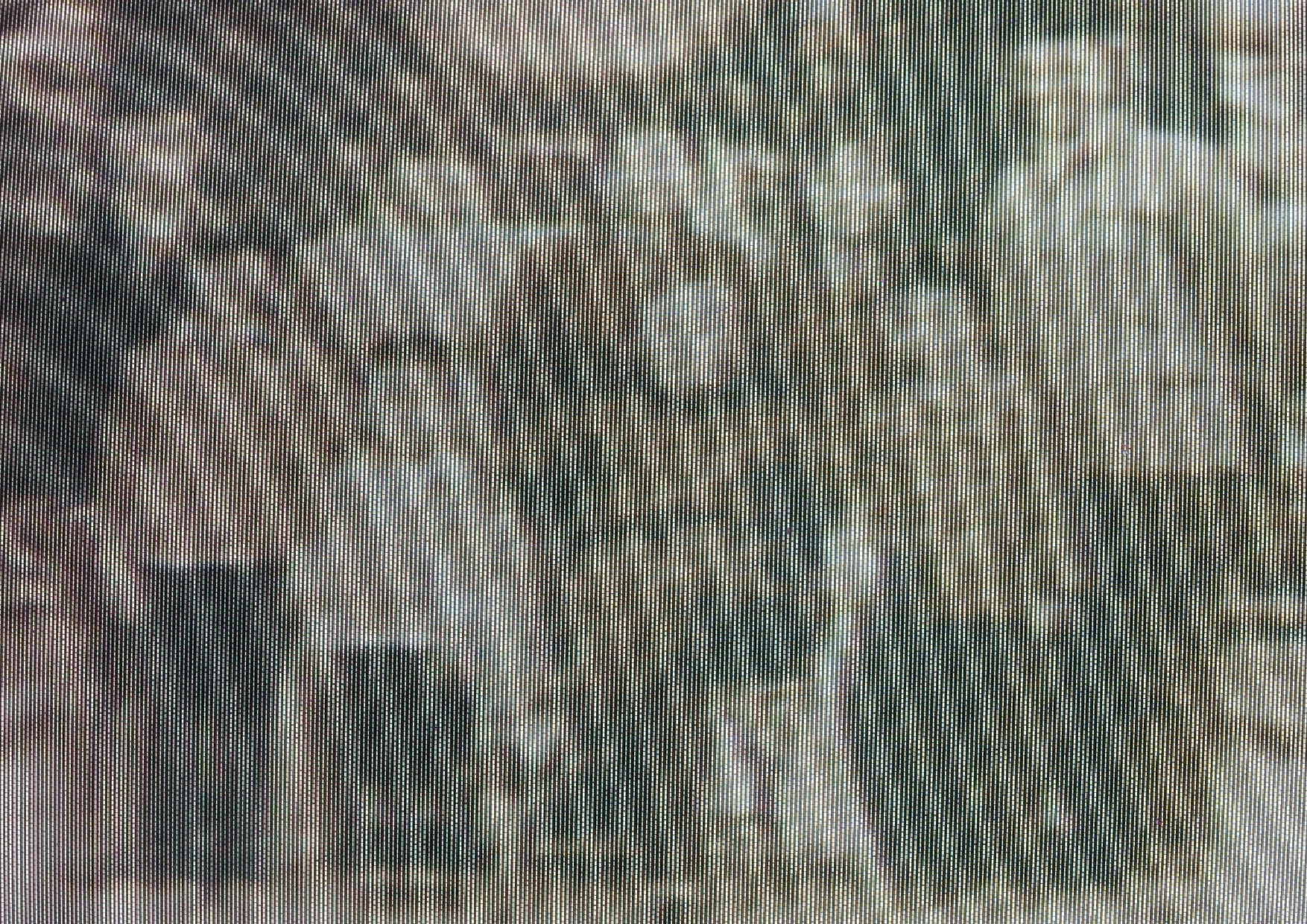

Using these recorded frequencies, I transformed the original photographs into a series of “memory portraits.” Images linked to stronger brainwave activity retain sharper detail, while those connected to weaker signals dissolve into blur. The scenes and figures from my past became like fragments of dreams translated into electrical traces, dispersed across each EEG chart.

Through this process, I was not only incorporating the theme of memory into photography, but also rethinking photography itself as a medium. Photography does not merely document external appearances; it also carries internal states — emotions, recollections, and thought processes. In this sense, the act of recording becomes inseparable from consciousness. The process itself constitutes the essence of this work.

Reflecting further, I began to see photography not simply as a tool for preserving reality, but as a means of engaging with time. The camera lens functions almost like a time machine, holding moments that might otherwise dissolve. Yet memory does not preserve time faithfully — it reconstructs, erodes, and reshapes it.

As the son of a doctor and a physics teacher, I was fortunate to receive their support in conducting the EEG experiment and transforming the original images. The work thus carries a quiet circularity: memories formed in the presence of my parents gradually faded with time, only to be reactivated and reinterpreted with their assistance once again.

Yet this work is not about nostalgia. It is an inquiry into memory, time, and existence — into how time simultaneously erodes and constructs us, how memories form and dissolve, and how life unfolds in a continuous oscillation between fading and becoming.

This encounter prompted me to question the nature of memory itself: What constitutes a portrait of memory? How can its essence be captured or recorded? These questions became the starting point of my visual exploration of “memory,” leading me to experiment with photography and portraiture as a way of approaching the invisible.

In pursuit of this idea, I underwent electroencephalography (EEG) at the hospital where my mother worked. As I recalled the childhood photographs, the EEG recorded the frequencies of my brainwave activity associated with memory. Stronger memories produced clearer, more pronounced waveforms, while weaker ones appeared faint and diffused.

Using these recorded frequencies, I transformed the original photographs into a series of “memory portraits.” Images linked to stronger brainwave activity retain sharper detail, while those connected to weaker signals dissolve into blur. The scenes and figures from my past became like fragments of dreams translated into electrical traces, dispersed across each EEG chart.

Through this process, I was not only incorporating the theme of memory into photography, but also rethinking photography itself as a medium. Photography does not merely document external appearances; it also carries internal states — emotions, recollections, and thought processes. In this sense, the act of recording becomes inseparable from consciousness. The process itself constitutes the essence of this work.

Reflecting further, I began to see photography not simply as a tool for preserving reality, but as a means of engaging with time. The camera lens functions almost like a time machine, holding moments that might otherwise dissolve. Yet memory does not preserve time faithfully — it reconstructs, erodes, and reshapes it.

As the son of a doctor and a physics teacher, I was fortunate to receive their support in conducting the EEG experiment and transforming the original images. The work thus carries a quiet circularity: memories formed in the presence of my parents gradually faded with time, only to be reactivated and reinterpreted with their assistance once again.

Yet this work is not about nostalgia. It is an inquiry into memory, time, and existence — into how time simultaneously erodes and constructs us, how memories form and dissolve, and how life unfolds in a continuous oscillation between fading and becoming.